PID Control

PID is a method of moving a mechanism to a precise point. It works using a Proportional, integral, and derivatie term. Let's dive deeper into each of these terms and what they do.

The kP term

the P term, or the Proportional term, is the most commonly used term for PID. To explain how it works, let's use an example mechanism that has to move 50 degrees. Using an encoder value on the mechanism, we know that the mechanism's current position is at 0 degrees. We also know the mechanism needs to get to the 50 degree position. This distance is called the error. So, the mechanism has an error of 50 degrees.

The proportional term is a constant, and it works by multiplying itself by the error to get the motor output. The equation is:

MotorOutput = kP * Error

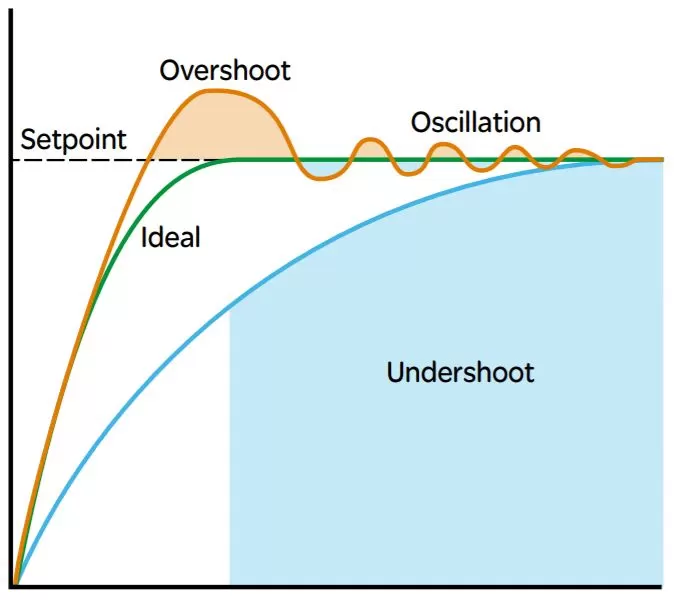

The P term is quite straightforward. as the motor moves the mechanism closer to its 50 degree mark, the error becomes smaller, and the motor output will then slow as the mechanism gets closer to the goalpoint. Here is a graph with what different PID values may do to a mechanism in relations to the setpoint:

Tuning the kP term

As said before, it is important to start with a small kP term. Having one that is too large can lead to extremely high speeds and oscilation that may break a mechanism. Let's go back to our mechanism example. at first, we decide to test it with a kP value of 0.05. After running it, we get a result that looks similar to the undershoot in the graph above. So, we decide to increase the kP value to 0.1, resulting in a graph that looks similar to the overshot. So, after decreasing kP to 0.075, our result is almost to perfection.

kS and kG terms

While ks and kg are not in the PID acronym, they are equally as important, and for several reasons.

kS

So far learning about the P term, we have left out a very important

outside force that will affect the movement of a mechanism: friction. Imagine you had a block that you needed to push across the floor. In a frictionless world, pushing

the block would be effortless. However, in the real world, we do have friction, meaning you need to push harder the more friction there is. Then, imagine you need to push

this block backwards. You will experience that same frictional force either way. In robotics, that also true. Imagine a motor pushes a block by recieving a positive output.

Then imagine that motor has to pull that block with a negative output. Either way, you have to add on the value to overcome friction. That is what ks is, the force necessary to overcome

friction, and it is added or subtracted from output, depending on its sign. The mathematical equation to represent this is Motor output = output + ks * sgn(output).

kG

kg is the constant that represents the force needed to "hold" against gravity. Because all mechanisms have weight, a kG constant is needed to remove the effect weight has, allowing for a cleaner system. Factoring this constant in is simple, and can be done with this equation:

Motor output = output + kg

Special cases: Arm

While the previous equation works fine for something like an elevator, an arm is a bit more tricky. Imagine this. You are holding a steel pole from one of the ends. Holding it straight out is much more difficult than holding

it vertical. This change in difficulty is reflected in a change in kg. The equation for this is kg term = kg * cos(theta). In this situation, An arm straight up represents 0 degrees, an arm straight out represents 90 degrees,

and an arm straight down represents 180 degrees. This works because the cosine of 90 is 1, and an arm that is straight out has the maximum force of gravity acting on it. Additionally, the cosine of 0 or 180 is 0, and when the arm is

straight up or straight down, gravity would have no effect on the system.

Calculating ks and kg

Manual calculations for these values can be done at the same time for an elevator like this:

- Increase voltage to the motor until the elevator just barely begins to move up.

- Then, Decrease voltage to the moter until it just barely starts to move down.

- Your kg can be found by averaging the two voltages, and ks can be found by finding half the difference of them. This works because directly in the middle of slightly up and slightly down is perfectly stationary, or what the elevator is doing with the voltage supplied by kg, and half the difference of slightly up and slightly down is the value needed to overcome friction and allow the system to move from stationary, or ks. In the case of an arm, place the arm out so it is perfectly horizontal (or as close to it as you can), and do these tests in that orientation to find the value of ks and kg.

Is kg Always needed?

No, it's not. In some systems, kg is not needed, because only friction is affecting the system. Some examples of these would be a turret or horizontal slide (an elevator on it's side).